Ad Viewability: What Is It And Does It Really Matter?

Get helpful updates in your inbox

Procter & Gamble announced at the IAB Annual Leadership Meeting in 2017 that they were cutting their programmatic ad spend by 90%. As the world’s largest advertiser who spend 6 billion dollars a year, this came as a shock to the industry. Marc Pritchard, Chief Brand Officer of Procter & Gamble, cited the driving factors behind the cuts were issues and a lack of transparency with third-party measurement, fraud, ad viewability, and brand safety.

In the years since the announcement, one of those issues has been a hot topic and a metric touted by publishers and ad ops shops alike—ad viewability. Even video advertising company Teads announced in 2019 that they would only charge brands for viewable impressions, and are guaranteeing 100% viewability.

Today, I’m going to walk you through the ins and outs of ad viewability. But more importantly, I’ll show you why it’s far from the be-all-end-all of advertiser metrics, and how publishers over-optimizing for viewability harm both user experience and how advertisers bid over time on their websites.

We also have a video on ad viewability available on our YouTube channel.

What is ad viewability?

Ad viewability—or a ‘viewable ad impression’ is defined as more than 50% of the ad pixels for more than 1 second is counted as a viewable impression.

This article on CNN shows that the top of page and sidebar ad units would be counted as a viewable impression if the user didn’t scroll away from the ad in less than one second. So, these two ads impressions would earn the publisher money, and the advertisers are happy because the ads served count as viewable.

It’s well known that ad units that are considered “above the fold” are often the most valuable. Meaning they are visible when the page loads for the visitor.

Viewability sounds straightforward enough, right? Not so fast. When Procter & Gamble cut their ad budget, they provided some additional data on the issue of viewability.

“The average ad is viewed for 1.7 seconds and that only 20 percent of ads are viewed for two seconds, the minimum standard for viewability, according to the Media Rating Council.”

So that means that 80% of users must be scrolling quickly enough to remain under 2 seconds. This type of data is frustrating to advertisers who shell out billions of dollars per year in advertising like P&G. They feel like they aren’t getting any bang for their buck, if any at all.

If ad viewability is low, and advertisers are going to reduce their ad spend because of it, what are publishers doing to combat low viewability?

What’s happening is that publishers (and sometimes, their ad ops contractors, or in-house teams) are creating forced viewability of ads. This phenomenon is becoming more common and ultimately, it actually harms ad rates if user experience metrics decline. That’s a fact.

What is forced viewability of ads?

Forced viewability of ads is when you’re preventing a user from being able to avoid seeing a ‘viewable’ ad and effectively ‘forcing’ a viewable ad into their viewport, no matter what the effect on the user.

For example: The CNN homepage loads, and after roughly 5 seconds, a large top of page ad loads and shifts the entire home page content down. If I were a visitor reading through some of the article titles, my experience would be jarred from the shift to say the least.

Another version of forced viewability you will see on sites across the web is how when you’re scrolling through content, there will be ‘sticky’ video ad units that appear within the content or in the sidebar, etc.

These sticky units follow the user down the page and continue playing until the ad is done or the user exits out of them.

Jamming ads in the page like this forces a delay in how the page loads; waiting for header bidders to load and loading up a video pop up, all causes the UX to be interrupted. As you can see, while I was trying to read even the title and the first paragraph the whole page jumped. This is bad because if a user is reading a paragraph, and suddenly it shifts, now they have to scroll around to find what they were just reading. That type of experience might cause a visitor to bounce away from the site.

As you can see – if I scroll slowly – it gives you an idea of how annoying this is for a user.

What is natural viewability of ads?

Natural viewability of ads is when the ads do not interrupt a user’s interaction with the content.

While we know that ads do have an effect on user experience, if done correctly, they can actually enrich the experience.

For example: Upon page load, when the user scrolls through the content, all the images and ads load without shifting the content around. This doesn’t distract and irritate the user.

Publishers should strive for natural viewability in stead of forced viewability. This is because forced viewability may give advertisers what they think they want “Wow, I’m getting great viewability from this publisher!”, but over time, when that site’s bounce rate increases, the visitor engagement decreases and return visitor rates drop; the ‘value’ derived from that ad drops. And when the value falls, conversions to those ads decrease, your ad rates are going to fall.

So, how did we get to this point, where advertisers like Procter & Gamble want better viewability, and publishers and ad ops shops are responding by forcing the viewability on visitors?

The history of ad viewability

The benefit of display advertising in its early days was that advertisers could track many different metrics about a user and an ad compared to traditional advertising. If you think about it, how can you measure the effectiveness of a billboard beside a road vs the customers who spent money? It’s almost impossible to know exactly how many people saw the billboard (and who didn’t) and try to gauge if that influenced results. That’s valuable knowledge lost.

So, when advertising budgets started being diverted away from hard-to-track media such as TV and Outdoor, advertiser’s adopted metrics that were very sharply focused on results, because everything online can be measured – down to the last pixel. The most popular measurement is called an ‘effective cost-per-acquisition‘ or eCPA (and can be calculated based on how much money was spent (how many impressions were bought, how much was spent on clicks, actions or registrations) and then dividing that total by the number of sales tracked.

For example: An advertiser – Netflix – is selling monthly subscriptions. So they serve display ads, and each time an ad is seen, they drop a cookie and uses optimized creatives for shows that a visitor might like (eg a TV show). Then, later on in the day, that same user goes to Netflix.com and signs up.

The advertiser’s just got what’s calling in the digital ad business as a ‘post-impression conversion’. The ad was ‘seen’ and the visitor was ‘converted’ to become a customer. Job well done, right?

Advertisers have been doing this for 10-15 years in the display ecosystem and the metrics used are called post-cookie, post-click, or post-impression tracking. The idea of a post-impression tracking cookie was popular, but Advertisers discovered that some publishers were putting multiple ads below the fold (just to drop a cookie) and that those ads were never being seen.

![]()

So advertisers then tried to work out the cost-per-acquisition numbers for their budgets:

- How much do we spend on advertising?

- How often are our ads being shown?

- And how many sign-ups (or conversions) occur?

The effectiveness of the ads are compared to how many cookies match and how much was spend on advertising.

Then, someone on the advertiser side thought of a brilliant idea. Let’s create a metric that shows whether the ad has been seen on the page. Everyone in the space agreed this was a good idea.

The creation of ad viewability metrics created a new demand…

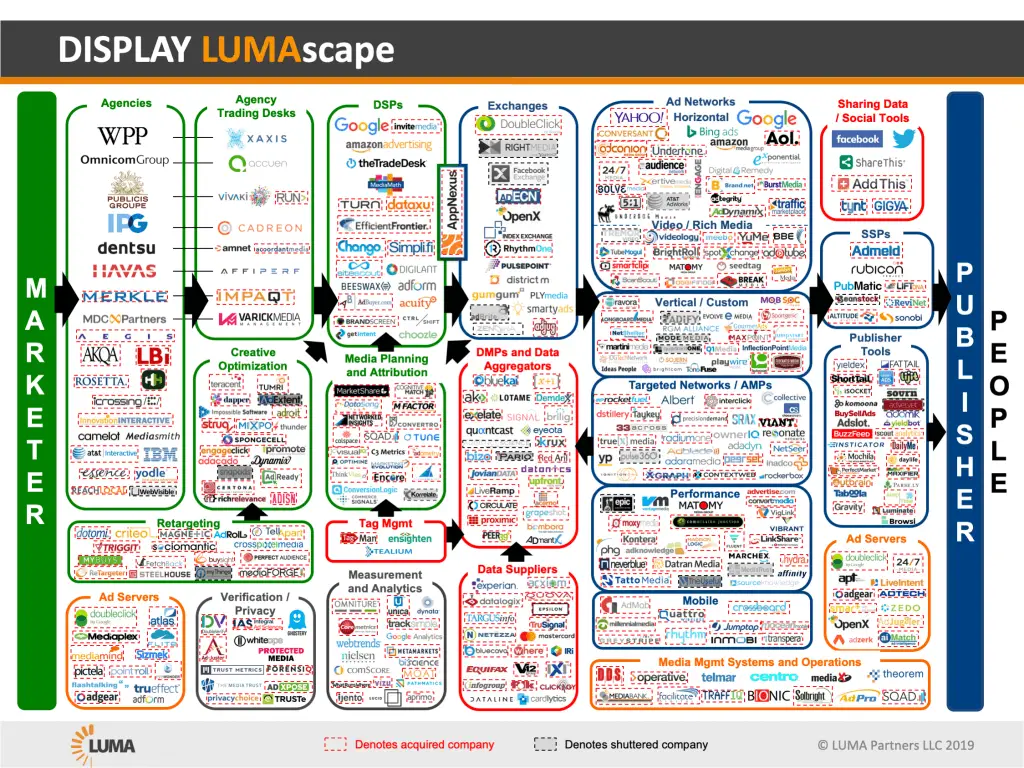

This demand for viewability caused a bunch of start-ups to appear in the market; these companies specialized in post-impression tracking and viewability and engagement monitoring. Many of these players can be found in the Display Lumascape under ‘verification’

Additionally, ad agencies sat as middlemen between advertisers (with the big budgets) and large publishing groups, like Hearst (with big audiences) to do the same thing.

These agencies and publishers ended up paying Double Verify (DV), MOAT (now owned by Oracle) and IAS to do tracking on whether the ads were viewable or not. They told the advertisers that they have been paying for a whole bunch of ad inventory that hasn’t even been seen and that it was absurd to pay for that.

Big advertisers buying brand awareness campaigns joined in, saying things like, “We are only going to buy ad inventory that is certified “viewable” or reaches a certain viewability percentage.” Even Google got onboard with this metric, starting to report on Viewability inside Google Ad Manager (GAM).

And that’s how the ad viewability metric was born and the definition decided as being as follows: “An ad is deemed viewable when more than 50% of the pixels can be seen in the viewport for more than 1 second”. Which brings us to where we are now. If advertisers are only going to pay for viewable impressions, what are publishers to do?

Well, the obvious temptation is to give the advertisers what they want and artificially create increased viewability by forcing ads on their visitors in places where they cannot be avoided (e.g. above the fold).

How are publishers artificially increasing ad viewability?

If you want to artificially increase your viewability, all you have to do is simply stop users from scrolling until the ad is loaded. Here’s another example of this:

You can see that when the home page loads, the content shifts down. If a user were trying to click on one of those sections, the button would disappear (Note: this example is also a highly dangerous practice with regards to Google Ad Placement Policy – because it could be encouraging accidental clicks on the ads.; when content is suddenly replaced with ads.)

In short, Publishers should think more strategically and long term and shouldn’t try to please advertisers by artificially increasing viewability. Forced viewability means engaging in practices that are bad for the user and stop them accessing the content easily.

Prioritizing the ad code to force viewable ads is bad for the publisher and will cost them money in the long run.

Why is that? One reason is SEO. If Google detects ‘bounces back to Google’ as part of their search satisfaction metrics, then these practices will certainly be a net negative on traffic over the long term.

For example: If a Google user is searching for something and selects your site to visit, but then bounces back to Google and searches for the same thing, that’s a black mark against your site. Why? because Google knows they didn’t get what they wanted first time around. If you do that for long enough and if your search satisfaction scores are worse than your competitors, your rankings will drop for that keyword.

So now artificially increasing viewability, by jamming up the page with ads, doesn’t sound like such a great idea any more?

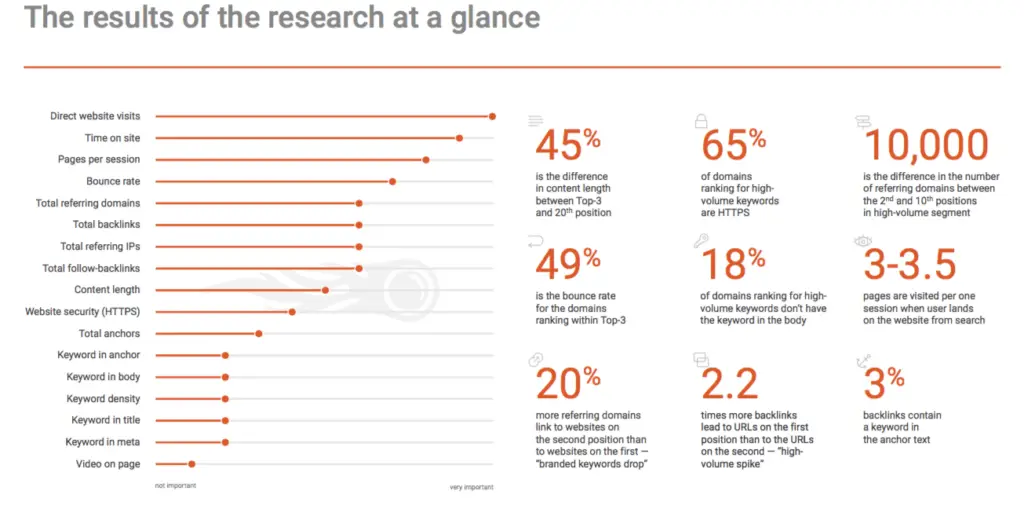

SEMRush ranks bounce rate as the fourth most important ranking factor for search after visits, session duration & pages per session.

As a publisher, if you’re putting anything in front of a user that’s preventing them from getting into the content, that’s bad for your bounce rates and bad for business. It’s a dangerous game to play because it might win you some short term revenue, but long term, it’s going to harm your site health, traffic and ultimately, revenue too.

How do you balance ad viewability and user experience?

The only way to balance ad viewability and user experience is through multivariate testing and personalization. Publishers who use Ezoic’s Ad Tester have the benefit of harnessing the power of A.I. to strike the right balance between revenue metrics and UX metrics.

If viewability and revenue were, in fact, directly correlated (they’re not!), then we would see Ezoic’s artificial intelligence system begin to prioritize high viewability ad units more and more. This is not (yet) the case. Ezoic’s machine learning system tests tens of thousands of different variables such as the number of ads on a page, number of ads within a user session, the ad sizes by viewport, the historical bounce rate of the landing page that the ads have been shown on before. Even metrics such as the time of day and the day of the week affect earnings and UX. In short – by personalising ad experiences and getting them to fit the natural UX of the site – you’ll get better results over time, regardless of their viewability metrics.

The takeaway here is that if you prioritize your visitors and treat them well, you’re going to make more money in the long run (and your visitors will be happier too!)

Publishers and ad ops shops who prioritize the advertiser metric of ad viewability are hemorrhaging their site’s value to advertisers. This might make a few extra dollars short term, but the advertisers won’t be fooled for long – jamming ads in and annoying users gets attention, but doesn’t develop true and natural ad value.

I’ve seen some ad ops shops that claim the ads served on their publishers’ sites get ‘very high viewability’. Well, that’s great. But what about bounce rates over time? The engaged time on page? and how are the pageviews per visit metrics trending?

These are all vitally important things to think if you’re a digital publisher. One thing Google is superb at, is figuring out what users want. And if you’re prioritizing the user, you’re going to be ahead of the curve compared to other publishers who choose to prioritize the advertiser.

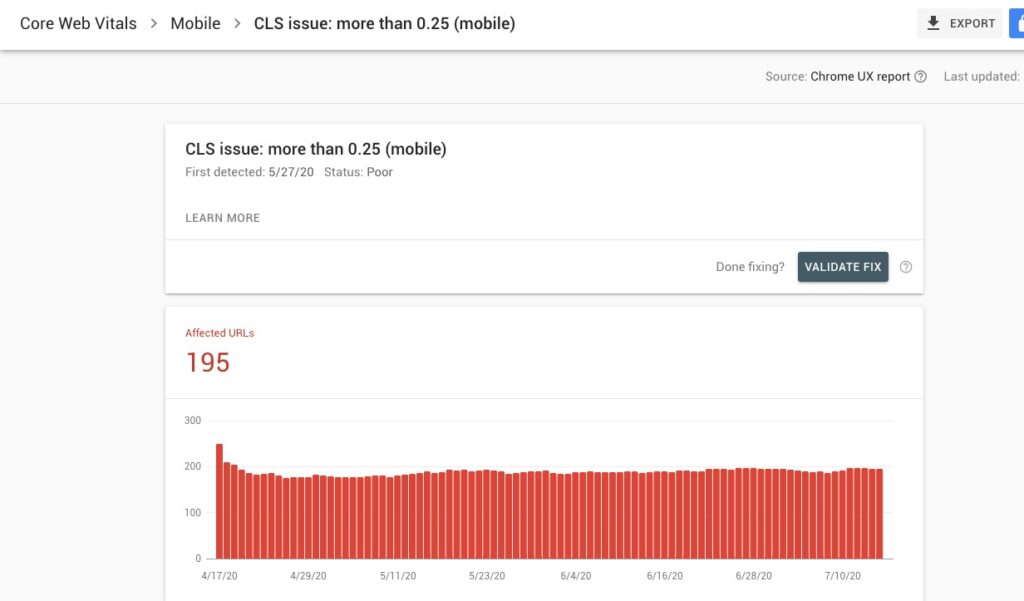

Google recently introduced the Core Web Vitals report in Google Search Console. The report is based on three metrics, and one of those is CLS: “Cumulative Layout Shift.” CLS is exactly what I described in this article—how often the layout shifts or “jumps” for the user.

Some of this info is also put into the Publisher Ads Beta section of Lighthouse Audits on Google Chrome.

Wrapping up ad viewability

With these ad viewability metrics, advertisers prefer them because they are only paying for viewability impressions. But at what cost to the user and the publisher?

To try to appease these viewability standards, publishers are inadvertently turning up the annoyance level of ads.

Is that behavior good for advertisers? In the long run, probably not. It’s just like if you watch a movie that has 20 ad breaks that increase in frequency towards the end and doesn’t allow you to fast forward because it’s free to view. A user might go somewhere else to find a streaming service with fewer ads. Just look at terrestrial TV and what happened to that industry.

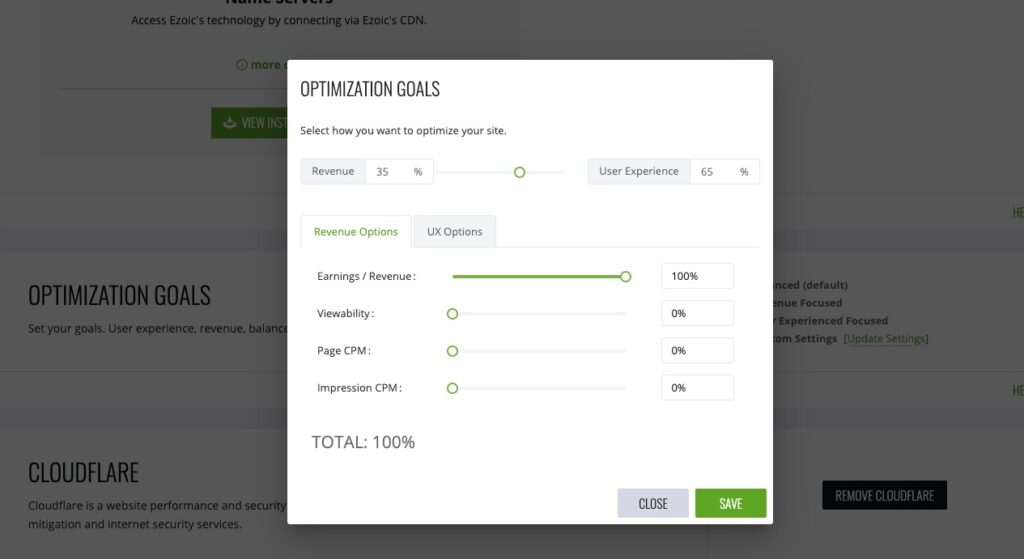

For publishers wanting to control their ad optimization goals, Ezoic gives you that ability. You can choose the percentages for weighting different metrics, and the A.I. will tailor the tests accordingly. As you can see below, publishers can choose between revenue and user experience (in this case 35/65) and also prioritize ad viewability, page and impressions CPM’s.

Some publishers may think that ad viewability is the most important metric and at first glance, it kind of makes sense. You’re going to give advertisers what they want and then your ad rates are going to go up. Right? Unfortunately, no – this is a complete fallacy. Because if you start to annoy the user, and the attention goes down even slightly, the quality of the attention will affect the quality of the price you’re going to get paid for the ad.

It’s important to note that not all of these types of high viewability ad units are bad – it can depend largely upon the viewport of the user. A big ad on a huge monitor might be fine for UX, but the same size ad on a small laptop might cause the bounce rates to increase. If you can treat users differently, then you can get high viewability and not harm UX.

When viewability is prioritized over user experience – that’s when you’re heading down the wrong path.

Visitor attention and engagement and ad revenue go hand in hand. Period. So, if you’re artificially jamming up pages with sticky ads, high-viewability ad units that pop out, or if you interfere with how a page loads to prevent users scrolling so you can force up your viewability scores, this is going to actually harm your earnings and traffic in the long run. Advertisers aren’t fooled for long and they will quickly reduce their bids on the low quality ‘forced’ viewabile impressions, in favour of higher quality users who see ads naturally alongside the content. Delivering good value for money to the advertisers and not gaming the system will benefit your Google rankings and your revenues over the long term.

Do you have any questions or comments about ad viewability? Let me know in the comments below:

John is the Chief Customer Officer of Ezoic. John was a founding Director of Media Run Group – which founded several online businesses in the mid 2000s (Media Run Search, Media Run Ad Network, and Blowfish Digital Ad Agency). Following the acquisition of Media Run Ad Network by Adknowledge Inc in Oct 2007, John managed the Adknowledge Social Games division in Europe prior to becoming a Director of Ezoic.

Featured Content

Checkout this popular and trending content

Ranking In Universal Search Results: Video Is The Secret

See how Flickify can become the ultimate SEO hack for sites missing out on rankings because of a lack of video.

Announcement

Ezoic Edge: The Fastest Way To Load Pages. Period.

Ezoic announces an industry-first edge content delivery network for websites and creators; bringing the fastest pages on the web to Ezoic publishers.

Launch

Ezoic Unveils New Enterprise Program: Empowering Creators to Scale and Succeed

Ezoic recently announced a higher level designed for publishers that have reached that ultimate stage of growth. See what it means for Ezoic users.

Announcement